To write the history of the Cunard Line in a few pages is to compress the history of the steamship itself.

In 1840 the majority of the world's deep sea trade was still carried in sailing ships. Steamships were proving themselves in coastal services, but there were few who would commit untried craft to the high seas.

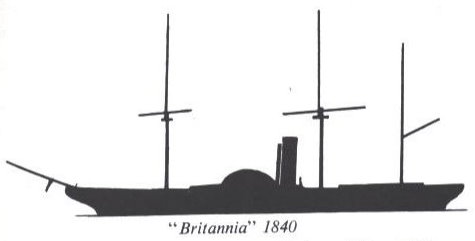

The “Britannia”, and her sister ships, the first regular Atlantic steamship service, were true pioneers. The “Britannia” was a wooden paddle steamer of 1,150 tons; her hull had a length of 207 feet. Artists striving to impress the size of the “Queens” soon found that “Britannia” could be fitted in the “Queen Mary's” main restaurant, or stowed on the foredeck of the “Queen Elizabeth”. The “Britannia” could carry 115 passengers and 225 tons of cargo at a speed of 9 knots.

Before she was completed estimates were worked out to see how much she would cost to run annually. The figures are interesting. Coal at 8s. a ton was cheap at Liverpool , but in Boston it was 20s. It was calculated that 6,960 tons of coal a year would be burned, that repairs would cost £2,000; lighterage, dock dues and pilotage, £700; dock labour, £500, and somewhere in the list there is a modest £100 for advertising.

It was announced that the “Britannia” would leave Liverpool on her maiden voyage to Halifax and Boston on 4th July 1840, American Independence Day. Detailed instructions for the voyage were handed to Captain Woodruff.

“The "Britannia” is now put under your Command for Halifax and Boston. It is understood you have the direction of everything and person on board. "

The First Engineer was to be allowed to have the general arrangement of all connected with the engine room. It was explicit that the sailors were to have no hand in the mysteries of steam. Conservation of fuel was a major problem. Bushel baskets were provided, each to contain 50 pounds of coal. At six every morning the engineers were to weigh 23 baskets, and to judge during the day the amount of coal that is being consumed. “Burn up all the ashes; throw nothing overboard. There are riddles on board.

Fourteen days and eight hours after leaving Liverpool the “Britannia” arrived in Boston to a tumultuous welcome, setting the pattern for many maiden voyage arrivals. Bostonians took to the “Britannia”. She was always given a welcome, and when the severe winter of' 1844 trapped the ship in the harbour ice, the citizens subscribed for the cutting of a seven-mile canal to the open sea.

The Cunard Line got off to a head start. Within ten Years its fleet was doubled, frequency of sailings were increased to once a week, New York was added to the itinerary, and a satisfied Admiralty agreed in 1847 to a new and increased mail subsidy of £173,340 a year. No small achievement for the young line. The charge of conservatism in its pejorative sense has been laid at the door of the Cunard Line. It is a fact that the line was slow in taking up new inventions, or processes, but the first requirement of safety influenced management not to adopt anything until it had been tested and proved. If, in the middle years, it cost some advance on competitors, the policy was proven by the safety record of the Cunarders, for not a single life was lost.

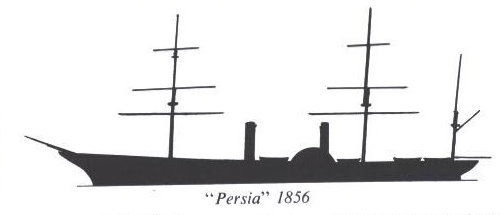

The Company was not in the lead with mail ships driven by propellers instead of paddles, and even in the 1850's when screw-driven Cunarders had been built, the paddle wheel was retained for the biggest ship of the decade next to the “Great Eastern.” This was the famous “Persia.” For one thing, the travelling public had the visible reassurance of power given by the thrashing paddlewheels, whereas they could not be certain that a propeller was turning properly.

The “Persia” did them proud her paddles were no less than 40 feet in diameter. In the sixteen years since the “Britannia” great strides had been made in size and power. The “Persia” was nearly twice the length of the “Britannia”; carried three times as many, passengers and had a speed of 14 knots compared with the “Britannia's” 9 knots. Her engines were five times the power of the “Britannia's,” but she burnt twice as much coal.

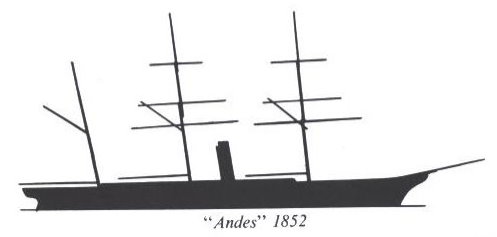

Meanwhile, the company had branched out into another service. The growing development of trade to the Mediterranean lured the MacIver brothers, who were Cunard's Liverpool managers, and in 1853 a number of ships which had become outclassed on the Atlantic, were adapted for this new service. Soon the Atlantic ships had so grown in size that they were unsuited to the Mediterranean and specialised ships were built.

The Atlantic was fast becoming a ferry; so many ships began to appear in the 1850's, swelling the already considerable fleets of sailing ships, which continued to carry the bulk of the immigrant traffic. This was soon to change.

The big paddle wheelers were extravagant of space for their ungainly engines and for the stowing of the huge quantities of coal which they burned. The “Persia” could only carry one ton of cargo to every six tons of coal, which she consumed at the rate of 150 tons a day. Hence, in relation to their size the paddlers did not pull their weight economically. Passenger accommodation and cargo capacity were limited. The propeller-driven ship was not only cheaper to run, but machinery was more compact, freeing valuable space for revenue earning. Steerage accommodation for emigrant passenger began to appear in Cunard screw steamships, and as the numbers settling in America increased with every month, new ships were ordered, bringing the fleet to 26 ships by 1860.

How great had been the effects on the Atlantic trade, of the California gold rush in 1848, the repeal of the restrictive Navigation Laws in 1849, and the economic growth of America itself, can be judged from these figures. In the 30 years, 1815-1845, a million and a half emigrants entered the United States, whereas two arid a half million poured in during the following 20 years.

The year which saw the end of the American Civil War, 1865, brought the Cunard Line to its 25th anniversary; the “Great Eastern” was completing the laying of the Atlantic cable; and on 29th April the London papers which carried the first detailed reports of President Lincoln's assassination also published the obituary of Sir Samuel Cunard, who had died the previous day. Much had been archived during that quarter century. At sea, the steamship was throwing off the bonds that tethered it to sailing ship design.

In the Cunard Line, wooden hulls had been discarded after 1852, the paddlewheel in 1862, the clipper bow in 1867. Before long the iron hull was to give way to steel. Auxiliary sail alone remained; there had yet to come that absolute confidence in the reliability of the steam engine in all conditions of Atlantic weather.

The size of Cunarders was creeping up, bringing to passengers the advantages of greater comfort and to the company the problems of financing progressive larger and more complicated ships. In the 1870's the company lost some of the impetus which had kept it in the forefront of Atlantic lines. Competition was heavier.

To keep pace, there had to be financial reorganisation. Since 1840 the ownership of the company had come under the control of the three partners who had had the greatest part in its foundation.

In 1878 the partners' interests were consolidated when a joint stock company was formed with a capital of' £2,000,000. Of this, £1.200,000 was issued and taken by the families of' Cunard, Burns and MacIver as part payment for the property, and business transferred by them to the new company then established as the Cunard Steam-Ship Company Limited . Two years later the Cunard Line became a public company and the balance of the share capital was issued. The significance was contained in this sentence from the prospectus:

“…the growing wants of the Company's transatlantic trade demand the acquisition of additional steam ships of great size and power, involving a cost for construction which may, best he met by a large public company.”

The Directors were looking ahead to 1881, to the “Servia” the first Cunarder to be built of steel. Transatlantic steamships could now reach a speed of' 18 knots, a performance that meant improved timekeeping. Size, power and speed were now such that four ships could maintain a sailing schedule previously needing five ships. Once achieved, designers were to aim at three ships to do the work of' four. And ultimately was to be realised a weekly Atlantic service maintained by two large and fast ships.

Thus evolved the “Queens.” The ships were described by Sir Percy Bates as being “inevitable ships.”

The decade of the eighties was marked by another phenomenon of the Atlantic , which was to hold public interest for three quarters of a century – the Blue Riband. The publicity value of the fastest ship had already attracted many lines, but it was only at this period when so many ships had entered the lists, that the record began to pass, from ship to ship, in sonic cases at monthly intervals, and passages began to be measured in hour and minutes, as well its days. The Cunard Line never formally recognised the Blue Riband, asserting that it introduced an element of the race track, which could be at variance with principles of safety - but there was this admission: if the Blue Riband could be won in the normal course of a voyage, then it would be a valuable advertising point.

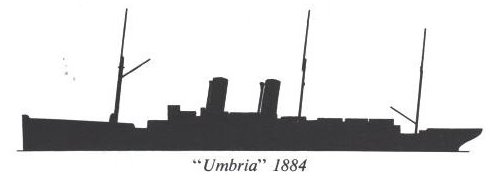

The first Cunard “18 knot ship” were the “Umbria” and “Etruria” of 1884, products of the reorganised Company. In their accommodation they aimed at taking away to sea essentials to Victorian living: heavily ornamented furniture and panelling, profusion of velvet drapes, and in the music room; stained glass cupolas, an organ and a piano.

In a sense, they were floating hotels: below decks, in the passenger accommodation there was little to suggest that only an inch of steel plate divided the dining room from the sea. But above decks, and in the working of the ship, watertight bulkheads, fireproof doors, two sets of steering gear - and above all - with a specification that exceeded Lloyd's requirements these ships were well out of the ordinary. They established the wisdom of building two big ships as twins, in terms of building costs and in performance. They so awed contemporary journalists that it seemed unreasonable to suppose they could be surpassed; much more powerful machinery could be installed, but there would be little room for passengers.

“The next great advance may therefore be sought rather in the direction of it new motive power in locomotion, rather than in any further development of steam engine”.

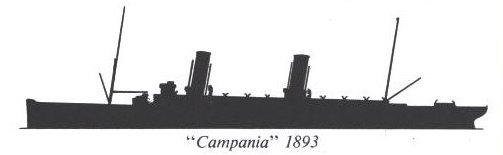

In 1886 two further “conventional” express ships followed the “Umbria” and “Etruria”, in 1893; the “Campania” and “Lucania.” They were driven by improved editions of the reciprocating engine. Sir Charles Parsons was experimenting with the steam turbine. More than half a century later, this form of propulsion is still the most economical and efficient for fast passenger liners. “Queen Elizabeth 2” is it turbine ship.

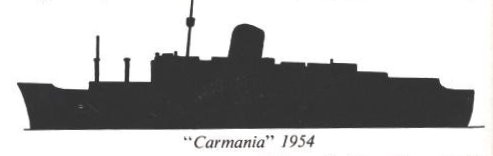

The early 1900s were years where the steam turbine became the “prime mover” for fast cross channel ships; it was applied, with caution, to intermediate Atlantic liners, which acted as floating test-beds for more ambitious ships. One such was the Cunarder “Carmania,” of l904. She was a turbine ship of 20,000 tons; an identical sister ship, “Caronia” was given reciprocating machinery. The “Carmania” proved beyond doubt that the turbine would be the right form of propulsion for the two giant ships then on the drawing board. They were “Mauretania" and the “Lusitania.”

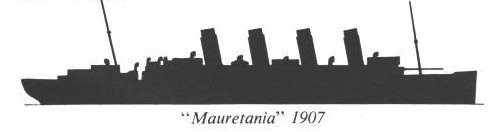

Of the two, the “Mauretania” has passed into British maritime history as the ship, that by performance rather than by sheer size, kept up her passenger numbers throughout her life, and, as sometimes happens with ships, grew faster as she grew older. The birth of these two ships was not easy.

In 1902, Pierpont Morgan's International Mercantile Marine had swallowed many Atlantic lines, and had eyes on Cunard. The British government viewed the prospect with disquiet, for the White Star Line had already been absorbed. Lord Inverclyde , Cunard chairman at the time, was well aware an isolated Cunard Company could not hope to hold its own against such a mammoth consortium unless it was equipped with new, and very large and fast ships. An outcome of negotiations was a government loan of £2,600,000 over 20 years at 2¾ per cent, which opened the way for the “Mauretania” and “Lusitania” to be built.

Two years were spent on developing and perfecting their design. The basic requirement was a ship capable of maintaining an average speed of 25 knots. It was estimated that at full power as much as 1,000 tons of coal a day would be consumed; bunker space had to be allocated for upwards of 6,000 tons. Obviously the ships had to be big enough to accommodate the large numbers of passengers they would need to carry to pay for the speed; but dimensions were limited by, dock and harbour facilities at the terminal ports of Liverpool and New York .

Twenty five years later, when plans were on the drawing board for the “Queens”, these were problems that were repeated almost exactly. In 1903 a committee of experts was established to solve these problems and the choice of propelling machinery. One proposal was to play safe and stick to the well tried reciprocating engine, by installing huge five-cylinder engines driving three propellers. But the success of the “Carmania's” turbines won the day, and steam turbines and four propellers were adopted. Three tenders were invited; from Newcastle, Barrow and Clydebank . The hull dimensions proposed by each yard were very close: Newcastle, length 760 feet and breadth 80 feet; Barrow, 760 feet and 78 feet, Clydebank, 730 feet acid 78 feet. One bonus came later - an extra foot on draught, made possible by additional dredging of the approach channels to New York . As it was, the final design worked out to a length of 790 feet and a breadth of 88 feet, a substantially larger model, which resulted in a gross tonnage of over 30,000 tons, making the two ships the largest in the world.

One outcome of the International Mercantile Marine (IMM) was an international free for all in passage fares. Passenger fares had decreased to as little as £6 for a passage to New York. The conference table was the logical answer and the lines, suffering from nothing less than civil war, met together to work out a reasonable solution.

In 1907 the Cunard Company was in a strong position. It had eluded the clutches of the IMM and brought its leading ships into a position which restored them as “first liners.” Further, a counter move against the IMM in 1903 resulted in the creation of a new and profitable source of revenue. By agreement with the Hungarian government, European immigrants, a guaranteed 30,000 a year, travelled in Cunard liners from Fiume to New York.

The “Mauretania” and “Lusitania” both came into service in 1907, the “Mauretania” after a building period of only 29 months. Atlantic speed records fell to them; eventually the “Mauretania,” thoroughly run-in, set a performance that stood for 22 years, by averaging over 26 knots on a round voyage, a speed that was in excess of her contract average. One competitive reaction was to aim at size rather than speed, and as the short Edwardian period was ending, it brought to the Atlantic ships which could he described as “slow superliners.”

Cunard responded by building the “Aquitania”, a ship that exceeded the “Mauretania” in size by 15,000 tons, but not matching her in speed, and carrying an additional 1,000 passengers. How the two policies of size and speed would have developed is pure conjecture, for the First World War put an end to commercial rivalry.

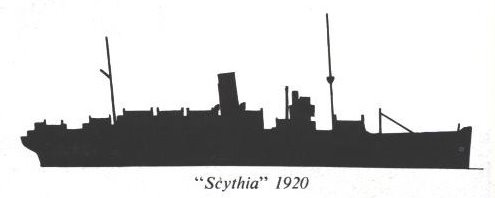

An immediate task for Cunard in 1918 was the restoration of a commercial fleet. In the condition of imbalance caused by war losses and by the allocation of German tonnage by way of reparations, this was onerous indeed. Cunard had the “Mauretania,” the “Aquitania,” and half the ownership of the “Imperator,” one of the German monster ships of over 50,000 tons, which had been renamed “Berengaria,” another, the “Bismarck” passed to the White Star Line as the “Majestic,” again on the basis of a 50% share with Cunard.

The arrangement was clumsy and was soon abandoned, each company accepting responsibility for one ship. With these three ships the Cunard Company was in a position to maintain its express service from Southampton to New York, supported by a postwar building programme of intermediate tonnage, which extended to the midtwenties and produced 13 ships totalling over 100,000 tons. Five main Atlantic routes were then serviced and included a new venture between Hamburg and New York, a profitable one in the absence of German tonnage during the first few years after the war.

The fact had to be faced that the “Mauretania,” “Aquitania" and “Berengaria” if not altogether obsolescent, would become outclassed by the early thirties. A period of intense economic nationalism set in; the Atlantic had become a prestige route. There were also changes in travelling habits. Holidays in America or in Europe were no longer confined to the rich; low fares in second and third class led to the coining of a new word, “tourist,” which has lasted; and the idea of pleasure cruising took hold.

Innovations of this kind meant better utilisation of tonnage, and winter cruising in particular, when Atlantic traffic was at its ebb, produced useful alternative revenue.

There were changes in ships. The steam turbine and watertube boiler together had been refined, partly as a result of experience with large and fast warships, and partly because of technical progress in the quality of steel. Bold thinking therefore had at its service technical know-how; but the sums had to be right before entering a commitment to build a superliner which could well cost upwards of £5 million, a considerable sum in the 1920s.

In planning the ship that was to be the “Queen Mary,” with the “Queen Elizabeth” an inevitable partner, a thrilling prospect was the possibility of a moneymaking weekly express service between Southampton and New York, operated by the irreducible minimum of two ships. Every week in the year (with the exception only of overhaul periods) one ship would leave Southampton, the other New York . To achieve it, the guaranteed service speed had to be 28 knots.

An irony of the “Queen Mary's” beginning was the coincidence of a world economic slump; work halted on the “Queen Mary” in December 1931 and for 27 months she lay on the stocks at Clydebank, a symbol of the malaise which was affecting all countries and all sea trades. But during this whole period foreign nations were going ahead with Atlantic superliners, most of them subsidised. There was here a proof that long views had to be taken on the tonnage needed to sustain a trade route where geographical distance and the extent of engineering expertise dictated the size of ships.

A weekly service could be operated from Southampton . Ports east of Cherbourg - for example, Hamburg and Bremerhaven , were not practical bases. Therefore, the Cunard Company was in the enviable position of being able to operate a weekly service, was convinced of the rightness of its decision to build two very large and fast ships, but was deprived of its time lead because of the bill market failure of 1931.

The “Queens” were not conceived as prestige ships. The prime reason for their building was summed up by Sir Percy Bates in a paradox:

“so far from attempting to construct steamers simply to compete with others in size or speed, the Cunard Company is projecting a pair of steamers which though they will be very large and fast, are in fact the smallest and slowest which can fulfil properly all the essential economic conditions. To go beyond these conditions would be extravagant, to fall below them would be incompetent, as the Company would be simply leaving to others a direct invitation to compete with it on more economic terms.”

Merger Between Cunard Line And The White Star Line

The eventual outcome, after Lord Weir had been asked by Neville Chamberlain to produce an assessment of the British position on the north Atlantic passenger routes, was the elimination of the wasteful competition which existed between the Cunard and White Star Companies. A condition of the Government loan which made it possible to complete the “Queen Mary,” and finance the “Queen Elizabeth” was a merger between the two companies.

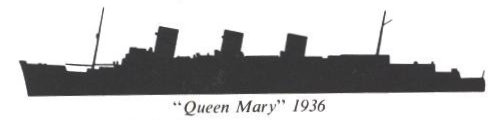

In 1934 Cunard and White Star emerged as Cunard White Star Limited, work was resumed on the “Queen Mary” and with it the morale of the shipbuilding and shipping industries was restored. By the time of her completion in 1936, the building programmes of foreign competitive companies had been completed, with the commissioning of such ships as the French Line's 83,000 ton “ Normandie, ” the Italian Line's “Rex” and “Conte di Savoia,” and earlier the German 50,000 tonners “Bremen” and “Europa.”

Improvement in transatlantic traffic also occurred, to the extent that the “Queen Mary” in 1937 and 1938 captured capacity numbers and with her performance in August 1938 placed herself as the fastest ship on the Atlantic.

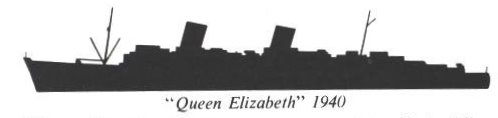

The centenary year of the Cunard Company was 1940. The second ship, “Queen Elizabeth,” was to join the “Queen Mary ” in the spring, and thereby set in motion the two ship weekly service, first planned when preliminary sketches for the “Queen Mary” appeared in 1926. This commercial partnership was not achieved until 1947, when both ships had been reconditioned after their war service. Concurrently there had been a process of fleet renewal which added 15 ships of a total gross tonnage approaching 200,000. This was a period of pent-up demand for Atlantic travel; there was a renewal of the flow of emigrants to Canada; Europe with reopened frontiers was eager to receive overseas visitors. The “Queens” and the new Cunarders were poised to carry them.

This was a period of boom for all the Atlantic lines. Still to come was the transition period when the jets began to erode the sea carriers' long entrenched position. There had to be rethinking about the function of the passenger ship. From a pattern of all year round service on a fixed route, there developed the dual-purpose ship, capable of meeting the demands of a seasonal trade and of cruising when traffic fell away.

So rapid were the technological advances of the late 1950's that the need for what might be described as a “scheduled service” ship disappeared, and the Q.3, limited by sheer size from becoming the flexible ship, was abandoned. She had been planned as an extension of the “Queens," capable of carrying slightly more passengers, at 30 knots on the Atlantic during the season, with winter cruising regarded as a secondary function.

Technological change in the one decade between 1950 and 1960 exceeded by great bounds what had been achieved in 1920 and 1940. Who in 1950 would seriously have supported the idea that man might land on the moon before 1970? The ship that began to take shape on Cunard drawing boards was a ship entirely different from the “Queens”; and in her evolvement, designers were helped by experience of operating the “Carmania” and “Franconia.”

These ships had begun life in the middle 1950's on the Canadian service but had no specifically styled cruising features. They were converted to dual purpose ships in 1963, with big open air lido decks and swimming pools; public rooms and cabins were redesigned; air conditioning was installed; they emerged as new ships. Thus has the Cunard Company moved with the times?

With “Queen Elizabeth 2” as a great new ship, and with “Franconi” and “Carmania” giving magnificent support, the Cunard Line will be marketing transatlantic services in the atlantic season, still preserving, in association with the French Line's “France,” a weekly service when it is needed; “Carmania” and “Franconia” will work either separately or together as cruise liners. Given three ships of this flexible character, and with an almost infinite number of holiday combinations possible, including air/sea patterns, Cunard is well set for full speed ahead. |